Writing resources for Myth-Folklore and Indian Epics at OU. :-)

Showing posts with label Writing Mechanics. Show all posts

Showing posts with label Writing Mechanics. Show all posts

Wednesday, January 22, 2020

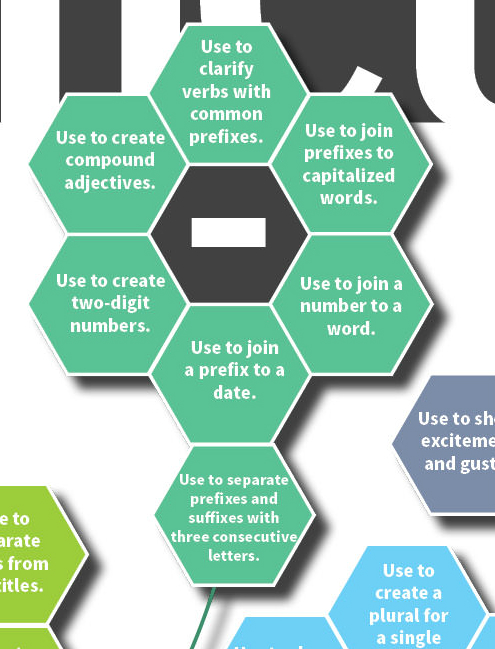

69 Rules of Punctuation

What an amazing infographic! It's from Curtis Newbold, The Visual Communication Guy. Click on this image for a large view, or use the detail snippets below.

Detail snippets:

Labels:

graphics,

Infographics,

mechanics,

recycle,

Writing Mechanics

Wednesday, August 31, 2011

Comma Splice (Run-On Sentence)

A run-on sentence is when you have two (or more) independent clauses that are run together in a single sentence. You can use conjunctions to coordinate the clauses (see below) or you can use some creative punctuation (again, see below) — but you cannot just use a comma. A comma is not enough to join two independent clauses into a single sentence. When you try to use a comma to coordinate two independent clauses, the result is called a "comma splice" because the comma is being used to splice the two clauses together, and that is a task that the poor old comma cannot handle.

This sentence, for example, is a comma splice:

Robin Hood lived in Sherwood Forest, he was an outlaw.

Do you see the two independent clauses? Independent clauses are statements that can stand on their own as complete sentences, having both a subject and a verb:

SEPARATE SENTENCES. You can break the run-on sentence up into two separate sentences.

A better solution, however, is to find a way to express the close connection between the two sentences verbally. You can express the connection with a conjunction, either a coordinating conjunction like "and," "but," or "or" (putting the two statements on an equal level to each other) or a subordinating conjunction (which makes one statement into the main clause, while the other clause is secondary to it).

COORDINATING CONJUNCTION. When you join two independent clauses with a coordinating conjunction, you need to use a comma before the conjunction:

SUBORDINATING CONJUNCTION. When you use a subordinating conjunction, you have to decide which is the main clause and which is the subordinate clause.

The main clause does not have to come first, as you can see by comparing the two sentences below. In the first sentence, the main clause comes first, but in the second example the subordinate clause comes first and is separated from the main clause by a comma:

SEMICOLON. Finally, another way to express the close connection between two statements is to join them with a semicolon. Unlike a comma, a semicolon does indeed have the power to coordinate two independent clauses:

Comma splices and other kinds of run-on sentences are probably the single most common type of writing error that I see in the Storybooks. I hope these notes can help you to find and fix the comma splices in your own writing. If you have ideas about how I can improve the information provided here, please let me know!

This sentence, for example, is a comma splice:

Robin Hood lived in Sherwood Forest, he was an outlaw.

Do you see the two independent clauses? Independent clauses are statements that can stand on their own as complete sentences, having both a subject and a verb:

- Robin Hood lived in Sherwood Forest.

- He was an outlaw.

SEPARATE SENTENCES. You can break the run-on sentence up into two separate sentences.

- Robin Hood lived in Sherwood Forest. He was an outlaw.

A better solution, however, is to find a way to express the close connection between the two sentences verbally. You can express the connection with a conjunction, either a coordinating conjunction like "and," "but," or "or" (putting the two statements on an equal level to each other) or a subordinating conjunction (which makes one statement into the main clause, while the other clause is secondary to it).

COORDINATING CONJUNCTION. When you join two independent clauses with a coordinating conjunction, you need to use a comma before the conjunction:

- Robin Hood lived in Sherwood Forest, and he was an outlaw.

- Robin Hood was an outlaw, but he stole only from the rich and gave to the poor.

- You might have heard the story of how Robin Hood first met Little John, or perhaps that story is new to you.

SUBORDINATING CONJUNCTION. When you use a subordinating conjunction, you have to decide which is the main clause and which is the subordinate clause.

The main clause does not have to come first, as you can see by comparing the two sentences below. In the first sentence, the main clause comes first, but in the second example the subordinate clause comes first and is separated from the main clause by a comma:

- Robin Hood lived in Sherwood Forest because he was an outlaw.

- Because he was an outlaw, Robin Hood lived in Sherwood Forest.

SEMICOLON. Finally, another way to express the close connection between two statements is to join them with a semicolon. Unlike a comma, a semicolon does indeed have the power to coordinate two independent clauses:

- Robin Hood lived in Sherwood Forest; he was an outlaw.

Comma splices and other kinds of run-on sentences are probably the single most common type of writing error that I see in the Storybooks. I hope these notes can help you to find and fix the comma splices in your own writing. If you have ideas about how I can improve the information provided here, please let me know!

Labels:

mechanics,

Writing Mechanics,

Writing Tips

Tuesday, August 30, 2011

The Ten Rules of Quoted Speech

Unlike other kinds of writing you might do for school, storytelling thrives on quoted speech, also known as direct speech. In a traditional academic paper, indirect speech is the norm, but in a story it's easier and more natural to let the characters speak for themselves. So, if you are writing a story, you'll probably be using at least some direct speech. I hope this page will help you feel confident to do that, and if you have any questions that I have not answered here, please let me know!

Direct versus indirect. Direct speech means we get to hear the words as they come directly from the mouth of the character. In indirect speech, the words are reported in a subordinate clause. Direct speech uses quotation marks; indirect speech does not. If you compare direct versus indirect speech in these examples, I think you will see that direct speech is more clear, more succinct — and more alive!

As these examples show, indirect speech has complicated rules for how to change the verbs and pronouns from the direct statement into their indirect restatement. When you use direct speech, you don't have to change the words, but you do have to know how to use the punctuation marks that separate the quoted words from the rest of the story. The rules below explain just how to do that:

Rule #1: Use quotation marks for all direct speech.

When someone's words are repeated exactly as that person said or wrote them, you need to put those words in quotation marks:

Rule #2: Quotation marks are used in pairs.

There is an opening quotation mark that comes before the first word of the quoted speech, and then there is a closing quotation mark that comes after the last word of the quoted speech.

Rule #3: The first word of a quoted sentence is capitalized.

In quoted speech, just as in other forms of writing, you capitalize the first word of every sentence:

Rule #4: You can include multiple sentences inside a single set of quotation marks.

As long as the character is speaking, you can keep on quoting those words inside the same set of quotation marks. Here is an example where there are three sentences inside the quotation marks:

Rule #5: When the QUOTED SPEECH comes AFTER the verb of speaking, you use a comma after the verb of speaking and before the quoted speech.

Here's an example that shows quoted speech after the verb of speaking, with a comma between the verb of speaking and the quoted speech:

Rule #6: When the QUOTED SPEECH comes BEFORE the verb of speaking and the final sentence of the quoted speech ends with a PERIOD, you replace the period at the end of the final quoted sentence with a comma.

Here is an example where the quoted speech, ending with a period, comes before the verb of speaking. The period at the end of the quoted speech changes to a comma:

Rule #7: When the QUOTED SPEECH comes BEFORE the verb of speaking and the final sentence of the quoted speech ends with an EXCLAMATION MARK or a QUESTION MARK, you do NOT replace the exclamation mark or question mark with a comma.

Instead of replacing the exclamation mark or question mark with a comma, you just leave it unchanged. Here's an example with an exclamation mark:

Rule #8: You can split a quoted sentence into two parts that are wrapped around the verb of speaking.

When the quoted sentence is split, you put a comma after the first chunk of quoted speech, and you also put a comma after the verb of speaking clause. Here is an example:

Rule #9: Punctuation marks for quoted speech always go inside the quotation marks, not outside.

Here are some examples:

Rule #10: After you have closed a quotation in one sentence, you need to use a new set of quotation marks for quoted speech in the next sentence.

When you have a quoted sentence (or sentences) together with a verb of speaking, that is a complete sentence. As a result, you need another set of quotation marks to indicate quoted speech in the next sentence. Here's an example of a complete sentence using quoted speech:

As for the tortoise and the hare, I am sure you know what happened: the hare was not just confident — he was overconfident, and the tortoise turned out to be the winner of the race. Slow and steady wins the race. It applies to writing too: slow down, proofread, and make sure you are using the correct punctuation for the quoted speech in your stories. It's a winning strategy! :-)

Direct versus indirect. Direct speech means we get to hear the words as they come directly from the mouth of the character. In indirect speech, the words are reported in a subordinate clause. Direct speech uses quotation marks; indirect speech does not. If you compare direct versus indirect speech in these examples, I think you will see that direct speech is more clear, more succinct — and more alive!

| INDIRECT | DIRECT | |

| The hare said that he would challenge the tortoise to a race. | The hare said, "I will challenge the tortoise to a race!" | |

| The hare thought that he could beat the tortoise easily. | The hare thought, "I can beat the tortoise easily!" | |

| The hare asked the tortoise whether he would agree to a race. | The hare asked the tortoise, "Will you agree to a race?" |

As these examples show, indirect speech has complicated rules for how to change the verbs and pronouns from the direct statement into their indirect restatement. When you use direct speech, you don't have to change the words, but you do have to know how to use the punctuation marks that separate the quoted words from the rest of the story. The rules below explain just how to do that:

Rule #1: Use quotation marks for all direct speech.

When someone's words are repeated exactly as that person said or wrote them, you need to put those words in quotation marks:

- The hare said, "I will challenge the tortoise to a race."

- The hare thought, "I know I can beat the tortoise easily!"

- The tortoise pondered for a moment, grinned, and nodded slowly. "I accept your offer, Mr. Hare."

When you are writing dialogue, you will need to decide on the best mix of dialogue tags (words like "said," "asked," etc.) and dialogue beats (words that describe the action). Either way, the quoted words still go inside quotation marks.

Rule #2: Quotation marks are used in pairs.

There is an opening quotation mark that comes before the first word of the quoted speech, and then there is a closing quotation mark that comes after the last word of the quoted speech.

- The hare said to the tortoise, "You are so slow that I will beat you very easily."

In some fonts, you can see a slightly different shape used for the opening and closing quotation marks:

- The hare said to the tortoise, “You are so slow that I will beat you very easily.”

Rule #3: The first word of a quoted sentence is capitalized.

In quoted speech, just as in other forms of writing, you capitalize the first word of every sentence:

- "When should we do it?" asked the tortoise.

- The tortoise asked, "When should we do it?"

The word "When" is capitalized because it is the first word of a quoted sentence, even though it is not the first word of the main sentence.

Rule #4: You can include multiple sentences inside a single set of quotation marks.

As long as the character is speaking, you can keep on quoting those words inside the same set of quotation marks. Here is an example where there are three sentences inside the quotation marks:

- The hare said to the tortoise, "You are so slow that I will beat you very easily. In fact, I feel sorry for you because you are so slow. I know I will defeat you!"

Rule #5: When the QUOTED SPEECH comes AFTER the verb of speaking, you use a comma after the verb of speaking and before the quoted speech.

Here's an example that shows quoted speech after the verb of speaking, with a comma between the verb of speaking and the quoted speech:

- The hare said to the tortoise, "I challenge you to a race!"

Rule #6: When the QUOTED SPEECH comes BEFORE the verb of speaking and the final sentence of the quoted speech ends with a PERIOD, you replace the period at the end of the final quoted sentence with a comma.

Here is an example where the quoted speech, ending with a period, comes before the verb of speaking. The period at the end of the quoted speech changes to a comma:

- "I accept your challenge," the tortoise replied.

Rule #7: When the QUOTED SPEECH comes BEFORE the verb of speaking and the final sentence of the quoted speech ends with an EXCLAMATION MARK or a QUESTION MARK, you do NOT replace the exclamation mark or question mark with a comma.

Instead of replacing the exclamation mark or question mark with a comma, you just leave it unchanged. Here's an example with an exclamation mark:

- "I challenge you to a race!" the hare said to the tortoise.

- "When should we do it?" asked the hare.

Rule #8: You can split a quoted sentence into two parts that are wrapped around the verb of speaking.

When the quoted sentence is split, you put a comma after the first chunk of quoted speech, and you also put a comma after the verb of speaking clause. Here is an example:

- "I challenge you," the hare said, "to a race!"

Rule #9: Punctuation marks for quoted speech always go inside the quotation marks, not outside.

Here are some examples:

- Period: "I accept your challenge."

- Comma: "I accept your challenge," replied the tortoise.

- Question Mark: "When should we do it?" asked the hare.

- Exclamation Mark: "I challenge you to a race!" the hare said to the tortoise.

Rule #10: After you have closed a quotation in one sentence, you need to use a new set of quotation marks for quoted speech in the next sentence.

When you have a quoted sentence (or sentences) together with a verb of speaking, that is a complete sentence. As a result, you need another set of quotation marks to indicate quoted speech in the next sentence. Here's an example of a complete sentence using quoted speech:

- "I challenge you to a race!" the hare said to the tortoise.

- "I challenge you to a race!" the hare said to the tortoise. "You are so slow that I will beat you very easily. In fact, I feel sorry for you already because I know you will lose."

~ ~ ~

As for the tortoise and the hare, I am sure you know what happened: the hare was not just confident — he was overconfident, and the tortoise turned out to be the winner of the race. Slow and steady wins the race. It applies to writing too: slow down, proofread, and make sure you are using the correct punctuation for the quoted speech in your stories. It's a winning strategy! :-)

(image source)

Note: There are some other uses of quotation marks in English, such as "scare quotes" and the use of quotation marks with the titles of short works, like short stories or poems (Edgar Allen Poe's "The Raven," for example). Some of those other uses of quotation marks have different rules than the rules listed below. If you are looking for more information about all the different uses of quotation marks in English, Purdue OWL's Quotation Mark pages are very useful.

* * *

Due to the enormous number of spam comments by spellchecking and grammarcheck companies (a curse upon them all!), I have shut down comments on this post.

* * *

Due to the enormous number of spam comments by spellchecking and grammarcheck companies (a curse upon them all!), I have shut down comments on this post.

Labels:

mechanics,

Writing Mechanics,

Writing Tips

Monday, August 29, 2011

Quoted Speech: Paragraphs

When quoted words extend over more than one paragraph, you do not close the quote. Instead, put a new open quotation mark at the beginning of the second (or third or fourth) paragraph; that way the reader knows the same person is still speaking. Then, when the quote is finally over, you close the quote.

Here is an example of this use of quotation marks for quoted speech that extends over more than one paragraph:

Here you see Orpheus leading Eurydice out of the underworld; visit Wikipedia for more information.

Here is an example of this use of quotation marks for quoted speech that extends over more than one paragraph:

Orpheus's bride, Eurydice, died on their wedding day. Stricken with grief, he went down into the kingdom of the dead and persuaded Hades to return Eurydice to the land of the living. Hades agreed, but on one condition: Orpheus had to lead Eurydice out of the underworld without looking back to see her.

Orpheus began the journey with great joy. "Dear Eurydice," he said, "I could not live without you. Praise the gods for your deliverance! Just follow me, and we will return to the land of the living. (quote remains open)For more information, see the Rules of Quoted Speech.

"Have no fear! As we leave this gloomy world behind us, I will play for you on my lyre. Yes, I will sing a song of love for you, my beloved bride, and you will follow behind me, step by step. With words of joy, I will praise the gods for their gift of life." Yet as Orpheus began to sing, he realized that he had lost the power of song.

"Oh no!" he exclaimed. "What is happening? Somehow I cannot bring myself to sing in this darkness. I feel no joy in this gloomy mist; all I know is fear. (quote remains open)

"Dear Eurydice, are you there? Speak to me, my darling! Eurydice! Can you hear me? Are you there?" At that moment, Orpheus turned back . . . and lost his Eurydice forever.

Here you see Orpheus leading Eurydice out of the underworld; visit Wikipedia for more information.

Labels:

mechanics,

Writing Mechanics,

Writing Tips

Sunday, August 28, 2011

Commas and Vocatives

When you address someone directly in speech, that form of address is called a "vocative" (from the Latin verb vocare, to call out; compare the English word "invoke"). The vocative address is set off from the rest of the sentence with a comma (or with two commas if the vocative is inside the sentence). Here are some examples:

It is very important that you include the comma(s) in these sentences. If you do not include the correct punctuation, it can change the meaning of the sentence. Examples:

So, make sure you use the vocative comma wisely: the meaning of the sentence depends on it!

- The knights of the Round Table salute you, King Arthur!

- Lancelot, you must go and rescue Queen Guinevere!

- You are very wise, Merlin, but your knowledge has its limits!

It is very important that you include the comma(s) in these sentences. If you do not include the correct punctuation, it can change the meaning of the sentence. Examples:

- The hungry sailors said, "Let's eat Odysseus!" (This would mean the hungry sailors are cannibals, ready to eat Odysseus.)

- The hungry sailors said, "Let's eat, Odysseus!" (The comma lets us know that the sailors are speaking to Odysseus, inviting him to join in the meal.)

~ ~ ~

- Prince Charming shouted, "Stop Cinderella!" (The prince is ordering his servants to run after Cinderella and stop her before she escapes.)

- Prince Charming shouted, "Stop, Cinderella!" (Here Prince Charming is speaking directly to Cinderella, commanding her to stop.)

~ ~ ~

- On his way out of the bedroom, Paris said, "I will return Helen." (Paris must be speaking to himself; apparently he has decided to return Helen to her husband Menelaus in order to put an end to the Trojan War!)

- On his way out of the bedroom, Paris said, "I will return, Helen." (In this statement, Paris has no intention of returning Helen to her husband; instead, he is speaking directly to Helen, promising her that he will come back and dally with her later.)

So, make sure you use the vocative comma wisely: the meaning of the sentence depends on it!

On his way out of the bedroom,

Paris said, "I will return, Helen."

Paris said, "I will return, Helen."

Labels:

mechanics,

Writing Mechanics,

Writing Tips

Saturday, August 27, 2011

Commas and Interjections

When an interjection is used to express a strong emotion, it can stand alone with an exclamation mark:

Interjections: ah, alas, amen, aw, behold, boo, bye, cool, damn, darn, doh, duh, eek, eh, gosh, great, hah, ha ha, hail, hello, hey, hi, hmm, hurray, no, O, oh, oh dear, oh my, oh well, OK, okay, ooh, ouch, right, shh, so, tee-hee, thanks, ugh, uh, uh-oh, well, what, whoa, whoops, wow, yay, yeah, yes, yikes

I have not listed English swear words here. You can supply that list on your own! :-)

- Gosh! The Cyclops sure is big!

- Gosh, the Cyclops sure is big.

- Oh, I think the Cyclops is hungry.

- Hey, you better not bother the Cyclops!

- Hello, Mr. Cyclops! Please do not gobble us up.

- It looks like, hmm, the Cyclops is about to eat my friend. Oh no!

- The Cyclops has killed my friend, alas, and now he is after me! Eeeeek!

- You know that the Cyclops is seriously dangerous, right?

- Let's not bother the the Cyclops, okay?

Interjections: ah, alas, amen, aw, behold, boo, bye, cool, damn, darn, doh, duh, eek, eh, gosh, great, hah, ha ha, hail, hello, hey, hi, hmm, hurray, no, O, oh, oh dear, oh my, oh well, OK, okay, ooh, ouch, right, shh, so, tee-hee, thanks, ugh, uh, uh-oh, well, what, whoa, whoops, wow, yay, yeah, yes, yikes

I have not listed English swear words here. You can supply that list on your own! :-)

Labels:

mechanics,

Writing Mechanics,

Writing Tips

Friday, August 26, 2011

Uses of the Apostrophe

The apostrophe sign is used for two different purposes, contraction and possession.

Here are some examples of contraction, where the apostrophe takes the place of the missing letter or letters:

This is a painting of Ravana and Sita; see Wikipedia for more information (and yes, Ravana does have ten hands and twenty arms).

Here are some examples of contraction, where the apostrophe takes the place of the missing letter or letters:

- Rama didn't stop searching until he found Sita and rescued her.

(contraction: didn't = did not) - The people couldn't believe that Sita had remained faithful to Rama.(contraction: couldn't = could not)

- Sita, Rama's wife, was kidnapped by Ravana, the demon king.

(possession: Rama's wife = the wife of Rama, singular) - He carried her far away to Lanka, the demons' island.

(possession: the demons' island = the island of the demons, plural)

There are a few simple rules about how to use the apostrophe to indicate possession:

- For a singular noun, add apostrophe-s: Sita was Rama's wife.

(NOTE: When a singular noun ends in -s, you will sometimes see just an apostrophe instead of apostrophe-s, especially when the final syllable is not stressed. For example: Peleus was Achilles' father. In modern usage, though, you will also see apostrophe-s added even to words that end in an unstressed syllable. For example: Jesus's mother was named Mary. So, as a general rule, you should add apostrophe-s to any singular noun, even if it ends in s. Try pronouncing the word out loud: if you pronounce the apostrophe syllable as a separate syllable of its own, you should definitely add apostrophe-s!)

- For a plural noun that ends in -s, just add an apostrophe: Ravana carried Sita far away to Lanka, the demons' island.

- For a plural noun that does not end in -s, add apostrophe-s: Rama smiled when he saw his children's faces.

IMPORTANT NOTE. The apostrophe is NOT USED to indicate PLURAL NOUNS in English. When you want to create a plural noun in English, you add "s" - you do NOT add an apostrophe to create the plural form of a noun, even an unusual noun:

- Ravana and the other rakshasas lived on the island of Lanka.

(rakshasas, NOT rakshasa's)

- IT'S = "it is" but ITS = "belonging to it" (no apostrophe)

- THEY'RE = "they are" but THEIR = "belonging to them" (no apostrophe)

- YOU'RE = "you are" but YOUR = "belonging to you" (no apostrophe)

- WHO'S = "who is" but WHOSE = "belonging to whom" (no apostrophe)

This is a painting of Ravana and Sita; see Wikipedia for more information (and yes, Ravana does have ten hands and twenty arms).

Labels:

mechanics,

Writing Mechanics,

Writing Tips

Thursday, August 25, 2011

Semicolon

There are two main uses for the semicolon: (1) linking of independent clauses and (2) listing of items that contain commas.

(1) LINKING OF INDEPENDENT CLAUSES. The semicolon can be used to link two independent clauses. Examples:

When a conjunctive adverb connects two independent clauses in one sentence, it is preceded by a semicolon and followed by a comma (list of conjunctive adverbs). Examples:

Comma versus semicolon. You cannot use a comma to join two independent clauses. If you try to do that, the result with be a type of run-on sentence known as a "comma splice."

ERROR: Demeter is the goddess of agriculture, Persephone is her daughter.

You can correct this error by using a semicolon instead of a colon:

CORRECTED: Demeter is the goddess of agriculture; Persephone is her daughter.

Another option is to break up the run-on sentence into two separate sentences:

CORRECTED: Demeter is the goddess of agriculture. Persephone is her daughter.

Independent clauses only. If the two clauses cannot stand on their own as independent statements, then you cannot use a semicolon to join them.

ERROR: Ravana had many wives; although Mandodari was his favorite.

You can correct this error by using a comma instead of a semicolon:

CORRECTED: Ravana had many wives, although Mandodari was his favorite.

(2) LISTING OF ITEMS THAT CONTAIN COMMAS. You need to use a semicolon to separate items in a list when one or more of the items in that contain a comma. Examples:

Find out more about the semicolon here: SEMICOLON.

(1) LINKING OF INDEPENDENT CLAUSES. The semicolon can be used to link two independent clauses. Examples:

- Athena is the goddess of wisdom; Aphrodite is the goddess of love.

- The god Odin has two ravens, Huginn and Munin; their names mean "Thought" and "Memory" in English.

When a conjunctive adverb connects two independent clauses in one sentence, it is preceded by a semicolon and followed by a comma (list of conjunctive adverbs). Examples:

- Vishnu is famous his many avatars; for example, Rama and Krishna are both avatars of Vishnu.

- The lion is king of the beasts; nevertheless, he needed the help of a tiny mouse to escape from the hunter's net.

Comma versus semicolon. You cannot use a comma to join two independent clauses. If you try to do that, the result with be a type of run-on sentence known as a "comma splice."

ERROR: Demeter is the goddess of agriculture, Persephone is her daughter.

You can correct this error by using a semicolon instead of a colon:

CORRECTED: Demeter is the goddess of agriculture; Persephone is her daughter.

Another option is to break up the run-on sentence into two separate sentences:

CORRECTED: Demeter is the goddess of agriculture. Persephone is her daughter.

Independent clauses only. If the two clauses cannot stand on their own as independent statements, then you cannot use a semicolon to join them.

ERROR: Ravana had many wives; although Mandodari was his favorite.

You can correct this error by using a comma instead of a semicolon:

CORRECTED: Ravana had many wives, although Mandodari was his favorite.

(2) LISTING OF ITEMS THAT CONTAIN COMMAS. You need to use a semicolon to separate items in a list when one or more of the items in that contain a comma. Examples:

- Hercules battled many monsters: the Hydra, who had many heads; the Stymphalian birds, who were man-eaters; and Cerberus, the three-headed dog of hell.

- The animal avatars of Vishnu are Matsya, the fish; Kurma, the turtle; Varaha, the boar; and Narasimha, the man-lion.

Find out more about the semicolon here: SEMICOLON.

The god Odin has two ravens, Huginn and Munin;

their names mean "Thought" and "Memory" in English.

(image source)

their names mean "Thought" and "Memory" in English.

(image source)

Labels:

mechanics,

Writing Mechanics,

Writing Tips

Wednesday, August 24, 2011

Questions: Direct, Indirect, and Rhetorical

There are three types of questions in English: direct questions, indirect questions, and rhetorical questions. Direct questions and rhetorical questions have a question mark at the end, but indirect questions do not.

DIRECT QUESTIONS. Direct questions are actively soliciting an answer from the person who is being interrogated.

What is your name?

Where do you live?

How long have you lived there?

You also need a question mark when a direct question is being quoted:

“Will you walk into my parlor?” said a spider to a fly.

Till you try, you never know what you can do.

(Direct question: What can you do?)

RHETORICAL QUESTIONS. Rhetorical questions do not actually expect an answer. Instead, they are a way of making a statement without coming out and saying what you mean in the open. Sometimes rhetorical questions are sarcastic or provocative, but sometimes they are highly polite. Because rhetorical questions do have the same form as a direct question, they need a question mark at the end.

Did you really think I would believe your story?

Would you be so kind as to open the door for me?

~ ~ ~

DIRECT QUESTIONS. Direct questions are actively soliciting an answer from the person who is being interrogated.

What is your name?

Where do you live?

How long have you lived there?

You also need a question mark when a direct question is being quoted:

“Will you walk into my parlor?” said a spider to a fly.

(Details at the Proverb Lab.)

~ ~ ~

INDIRECT QUESTIONS. An indirect question reports a question, so it is a statement rather than a question. Even though it might contain a question word, the indirect question does not need a question mark at the end.

(Direct question: What can you do?)

One half of the world does not know how the other half lives.

(Direct question: How does the other half of the world live?)

Tell me why the ant midst summer’s plenty thinks of winter’s want.

(Direct question: Why does the ant midst summer's plenty think of winter's want?)

(Details at the Proverb Lab).

~ ~ ~

Did you really think I would believe your story?

Would you be so kind as to open the door for me?

Am I my brother's keeper?

(Details at the Proverb Lab.)

Labels:

mechanics,

Writing Mechanics,

Writing Tips

Tuesday, August 23, 2011

Active and Passive Verbs

There are two basic types of verbs in English: active verbs (transitive and intransitive) and passive verbs.

ACTIVE VERBS:

The subject of an active verb performs the action.

The Minotaur lives inside a labyrinth. [present tense]

The Minotaur lived inside a labyrinth. [past tense]

subject: Minotaur

verb: lives/lived

Theseus kills the Minotaur. [present tense]

Theseus killed the Minotaur. [past tense]

subject: Theseus

verb: kills/killed

Some active verbs are TRANSITIVE and some are INTRANSITIVE. A transitive verb is one that takes an object, while an intransitive verb does not have an object.

The verb "to kill" is transitive, which means it can take an object:

Theseus killed the Minotaur.

subject: Theseus

verb: killed

object: the Minotaur

The verb "to live" is intransitive, which means it cannot take an object:

The Minotaur lived inside a labyrinth.

subject: Minotaur

verb: lived

(no object)

PASSIVE VERBS:

When a verb is passive, it means that the subject of the verb does not perform the action. Instead, the subject is the object of the action.

The Minotaur is killed by Theseus. [present tense]

The Minotaur was killed by Theseus. [past tense]

subject: Minotaur

verb: is killed / was killed

(no object)

To put an active verb into the passive voice, you use the past participle along with a form of the verb "to be." Often the past participle ends in -ed as in these examples:

The Minotaur was killed by Theseus.

Theseus was helped by Ariadne.

Ariadne was abandoned by Theseus.

Sometimes, though, the participle is irregular and does not end in -ed:

The labyrinth was built by Daedalus.

Theseus was sent from Athens to Crete.

As a general rule in storytelling, you should use active verbs! This post contains some more examples: Examples of Active and Passive Verbs.

ACTIVE VERBS:

The subject of an active verb performs the action.

The Minotaur lives inside a labyrinth. [present tense]

The Minotaur lived inside a labyrinth. [past tense]

subject: Minotaur

verb: lives/lived

Theseus kills the Minotaur. [present tense]

Theseus killed the Minotaur. [past tense]

subject: Theseus

verb: kills/killed

Some active verbs are TRANSITIVE and some are INTRANSITIVE. A transitive verb is one that takes an object, while an intransitive verb does not have an object.

The verb "to kill" is transitive, which means it can take an object:

Theseus killed the Minotaur.

subject: Theseus

verb: killed

object: the Minotaur

The verb "to live" is intransitive, which means it cannot take an object:

The Minotaur lived inside a labyrinth.

subject: Minotaur

verb: lived

(no object)

PASSIVE VERBS:

When a verb is passive, it means that the subject of the verb does not perform the action. Instead, the subject is the object of the action.

The Minotaur is killed by Theseus. [present tense]

The Minotaur was killed by Theseus. [past tense]

subject: Minotaur

verb: is killed / was killed

(no object)

To put an active verb into the passive voice, you use the past participle along with a form of the verb "to be." Often the past participle ends in -ed as in these examples:

The Minotaur was killed by Theseus.

Theseus was helped by Ariadne.

Ariadne was abandoned by Theseus.

Sometimes, though, the participle is irregular and does not end in -ed:

The labyrinth was built by Daedalus.

Theseus was sent from Athens to Crete.

As a general rule in storytelling, you should use active verbs! This post contains some more examples: Examples of Active and Passive Verbs.

Theseus kills the Minotaur.

The Minotaur is killed by Theseus.

Theseus fighting the Minotaurby Étienne-Jules Ramey (1826).

Web Source: Wikipedia.

Labels:

mechanics,

Writing Mechanics,

Writing Tips

Monday, August 22, 2011

Examples of Active and Passive Verbs

Heroes just sound more heroic when you describe their accomplishments with active verbs! In fact, every story sounds better with active verbs. As a general rule, active verbs are a better choice 99.99% of the time when you are telling a story. So, use active verbs whenever you can! Here are some examples:

The head of the monster Medusa was chopped off by Perseus.

Perseus chopped off the head of the monster Medusa.

The robber Sciron was killed by Theseus by being pushed off a cliff.

Theseus killed the robber Sciron by pushing him off a cliff.

Phineas, king of Thrace, was rescued from the vicious Harpies by Jason.

Jason rescued Phineas, king of Thrace, from the vicious Harpies.

A golden sword was used by Heracles to cut off the last head of the Hydra.

Heracles used a golden sword to cut off the last head of the Hydra.

Penthesilea, queen of the Amazons, was defeated by Achilles.

Achilles defeated Penthesilea, queen of the Amazons.

The household gods of Troy were brought safely by Aeneas into Italy.

Aeneas safely brought the household gods of Troy into Italy.

The riddle of the Sphinx was answered correctly by Oedipus.

Oedipus answered the riddle of the Sphinx correctly.

If you would like to review the basic differences between active verbs and passive verbs, see this blog post: Active and Passive Verbs.

Here you see Perseus holding up the head of Medusa; visit Wikipedia for more information.

The head of the monster Medusa was chopped off by Perseus.

Perseus chopped off the head of the monster Medusa.

The robber Sciron was killed by Theseus by being pushed off a cliff.

Theseus killed the robber Sciron by pushing him off a cliff.

Phineas, king of Thrace, was rescued from the vicious Harpies by Jason.

Jason rescued Phineas, king of Thrace, from the vicious Harpies.

A golden sword was used by Heracles to cut off the last head of the Hydra.

Heracles used a golden sword to cut off the last head of the Hydra.

Penthesilea, queen of the Amazons, was defeated by Achilles.

Achilles defeated Penthesilea, queen of the Amazons.

The household gods of Troy were brought safely by Aeneas into Italy.

Aeneas safely brought the household gods of Troy into Italy.

The riddle of the Sphinx was answered correctly by Oedipus.

Oedipus answered the riddle of the Sphinx correctly.

If you would like to review the basic differences between active verbs and passive verbs, see this blog post: Active and Passive Verbs.

Here you see Perseus holding up the head of Medusa; visit Wikipedia for more information.

Labels:

mechanics,

Writing Mechanics,

Writing Tips

Sunday, August 21, 2011

Coordinating Conjunctions

There are three main coordinating conjunctions in English:

PUNCTUATION. When a coordinating conjunction is used to join two independent clauses, you usually want to have a comma before the conjunction:

SERIES. When you are joining more than two items, you use the conjunction to join the final two items; the other items are joined by commas.

BEGINNING A SENTENCE WITH AND. If you are tempted to use "and" at the beginning of a sentence, there is almost always a better alternative. Example:

The tortoise won the race. And all the animals were so proud of him!

BEGINNING A SENTENCE WITH BUT. If you are tempted to use "but" at the beginning of a sentence, there is almost always a better alternative. Example:

The hare lose the race. But he learned a good lesson.

"HOWEVER" IS NOT A COORDINATING CONJUNCTION. You cannot use the word "however" with a comma to coordinate two independent clauses.

The hare lost the race, however he learned a good lesson.

That is a type of run-on sentence called a "comma splice." To avoid this error, you need to use the word "but" as the coordinating conjunction, or you can use a semicolon instead of a comma.

Find out more here: CONJUNCTIONS.

- AND: This coordinating conjunction introduces an additional item: The tortoise and the hare are going to have a race.

- BUT: This coordinating conjunction introduces a contrasting item: The hare is fast but foolish.

- OR: This coordinating conjunction introduces an alternative item: Who do you think will win: the tortoise or the hare?

- NOR: This coordinating conjunction introduces a negated item: The tortoise is not boastful, nor is he lazy.

- YET: This coordinating conjunction introduces a contrasting item: The hare is fast, yet he loses the race.

- FOR: This coordinating conjunction introduces an explanatory item: The tortoise wins the race, for he is slow and steady.

- SO: This coordinating conjunction introduces a resulting item: The tortoise reached the finish line first, so he won the race.

PUNCTUATION. When a coordinating conjunction is used to join two independent clauses, you usually want to have a comma before the conjunction:

- The hare challenges the tortoise to a race, AND the tortoise agrees.

- The hare starts out ahead, BUT he stops to take a nap.

- The hare better wake up, OR he is going to lose the race.

- The tortoise AND the hare are going to have a race.

- The hare is fast BUT foolish.

- Who do you think will win: the tortoise OR the hare?

SERIES. When you are joining more than two items, you use the conjunction to join the final two items; the other items are joined by commas.

- The hare starts out fast, slows down, AND stops to take a nap.

- The tortoise starts out slow, never stops, AND wins the race.

BEGINNING A SENTENCE WITH AND. If you are tempted to use "and" at the beginning of a sentence, there is almost always a better alternative. Example:

The tortoise won the race. And all the animals were so proud of him!

- Try combining the sentence with the previous sentence by using a comma:

The tortoise won the race, and all the animals were so proud of him! - Try just leaving out the "and" completely:

The tortoise won the race. All the animals were so proud of him! - Try using a different word or phrase as the connector:

The tortoise won the race. Plus, all the animals were so proud of him!

BEGINNING A SENTENCE WITH BUT. If you are tempted to use "but" at the beginning of a sentence, there is almost always a better alternative. Example:

The hare lose the race. But he learned a good lesson.

- Combine the two sentences, and remember to use a comma before the "but" clause:

The hare lost the race, but he learned a good lesson. - Use a conjunctive adverb to connect the ideas, either in a single sentence or in separate sentences:

The hare lost the race; however, he learned a good lesson.

The hare lost the race. However, he learned a good lesson.

"HOWEVER" IS NOT A COORDINATING CONJUNCTION. You cannot use the word "however" with a comma to coordinate two independent clauses.

The hare lost the race, however he learned a good lesson.

That is a type of run-on sentence called a "comma splice." To avoid this error, you need to use the word "but" as the coordinating conjunction, or you can use a semicolon instead of a comma.

- The hare lost the race, but he learned a good lesson.

- The hare lost the race; however, he learned a good lesson.

Find out more here: CONJUNCTIONS.

The hare starts out fast,

but then he slows down to take a nap.

but then he slows down to take a nap.

Labels:

mechanics,

Writing Mechanics,

Writing Tips

Saturday, August 20, 2011

Correlative Conjunctions

Correlative conjunctions come in pairs; here are the most common correlative conjunction pairs:

As with coordinating conjunctions, no comma is required EXCEPT when the conjunctions are coordinating two independent clauses. In that case, you do need a comma:

Find out more here: CONJUNCTIONS.

- BOTH... AND...

Both Hathor and Isis are Egyptian goddesses. - NOT ONLY... BUT ALSO

Heracles is not only strong but also sneaky. - EITHER... OR...

Persephone spends her time either in the underworld with her husband Hades or on the earth with her mother Demeter. - WHETHER... OR...

Dasaratha must decide whether to make Rama king or to send him into exile. - NEITHER... NOR...

Neither Achilles nor Hector will survive the Trojan War.

As with coordinating conjunctions, no comma is required EXCEPT when the conjunctions are coordinating two independent clauses. In that case, you do need a comma:

- Heracles not only killed the Lernean Hydra, but he also killed the Nemean Lion.(Independent clauses: Hercules killed the Lernean Hydra. He killed the Nemean Lion.)

- Either Achilles is going to kill Hector, or Hector is going to kill Achilles.(Independent clauses: Achilles is going to kill Hector. Hector is going to kill Achilles.)

Find out more here: CONJUNCTIONS.

Persephone spends her time

either in the underworld with her husband Hades

or on the earth with her mother Demeter.

either in the underworld with her husband Hades

or on the earth with her mother Demeter.

(image source: Persephone and Hades)

Labels:

mechanics,

Writing Mechanics,

Writing Tips

Friday, August 19, 2011

Subordinating Conjunctions

The most complicated conjunctions to use are the subordinating conjunctions. Instead of joining two more-or-less equal things, subordinating conjunctions are used when there is an independent main clause (which can stand on its own), joined with a dependent subordinate clause (which cannot stand on its own). The conjunction expresses the relationship between those two clauses.

There are many subordinating conjunctions in English. Here is a partial list:

SENTENCE FRAGMENTS. A subordinated clause cannot stand by itself; it is just a sentence fragment, not a complete sentence.

- There might be a relationship in space.

Wherever Rama went in the forest, he found the ashrams of gurus and sages. - There might be a relationship in time.

Odysseus set sail for his home in Ithaca after the Greeks sacked the city of Troy. - There might be a logical relationship.

Even though the dwarves had warned her to be careful, Snow White ate the poisoned apple.

There are many subordinating conjunctions in English. Here is a partial list:

where

wherever

| before since when whenever while until as long as

once

now that

| since so that in order that why | though even though rather than while | if only unless until in case provided that assuming that even if whether | as though how |

Punctuation. When the subordinate clause comes first, there is almost always a comma between the subordinate clause and the main clause.

- Because Heracles was the son of Zeus and Alcmena, Hera hated him.

- Until a princess kissed him, the prince was cursed to remain a frog.

- After he had stolen the golden harp, Jack climbed back down the beanstalk.

- Provided that she did not stay past midnight, Cinderella was able to attend the ball.

- Hera hated Heracles because he was the son of Zeus and Alcmena.

- The prince was cursed to remain a frog until a princess kissed him.

- Jack climbed back down the beanstalk after he had stolen the golden harp.

- Cinderella was able to attend the ball, provided that she did not stay past midnight.

SENTENCE FRAGMENTS. A subordinated clause cannot stand by itself; it is just a sentence fragment, not a complete sentence.

- It was midnight and Cinderella had to leave the ball. Although she did not want to.

- It was midnight and Cinderella had to leave the ball, although she did not want to.

Labels:

mechanics,

Writing Mechanics,

Writing Tips

Thursday, August 18, 2011

Conjunctive Adverbs

Conjunctive adverbs are words and phrases that can be used to join two independent clauses. When a conjunctive adverb connects two independent clauses in one sentence, it is preceded by a semicolon and followed by a comma. For more information about this use of the semicolon, see the Semicolon page. Examples:

Find out more about here: CONJUNCTIVE ADVERBS.

- Vishnu is famous his many avatars; for example, Rama and Krishna are both avatars of Vishnu.

- The lion is king of the beasts; nevertheless, he needed the help of a tiny mouse to escape from the hunter's net.

- The Hydra was a savage beast with many heads. Nevertheless, Heracles was able to defeat and kill the monster.

- Athena was the Greek goddess of wisdom. In addition, she was also a goddess of warfare.

- The god Shiva is famous for his dancing. Indeed, he is sometimes referred to as Nataraja, "Lord of the Dance."

- Aesop was born into slavery. Eventually, however, he won his freedom.

- The dove is a symbol of peace. The eagle, in contrast, is a symbol of war.

| addition | again, also, and, and then, besides, equally important, finally, first, further, furthermore, in addition, in the first place, last, moreover, next, second, still, too |

| comparison | also, in the same way, likewise, similarly |

| concession | granted, naturally, of course |

| contrast | although, and yet, at the same time, but at the same time, despite that, even so, even though, for all that, however, in contrast, in spite of, instead, nevertheless, notwithstanding, on the contrary, on the other hand, otherwise, regardless, still, though, yet |

| emphasis | certainly, indeed, in fact, of course |

| example or illustration | after all, as an illustration, even, for example, for instance, in conclusion, indeed, in fact, in other words, in short, it is true, of course, namely, specifically, that is, to illustrate, thus, truly |

| summary | all in all, altogether, as has been said, finally, in brief, in conclusion, in other words, in particular, in short, in simpler terms, in summary, on the whole, that is, therefore, to put it differently, to summarize |

| time sequence | after a while, afterward, again, also, and then, as long as, at last, at length, at that time, before, besides, earlier, eventually, finally, formerly, further, furthermore, in addition, in the first place, in the past, last, lately, meanwhile, moreover, next, now, presently, second, shortly, simultaneously, since, so far, soon, still, subsequently, then, thereafter, too, until, until now, when |

Find out more about here: CONJUNCTIVE ADVERBS.

The Hydra was a savage beast with many heads.

Nevertheless, Heracles was able to defeat and kill the monster.

(image source)

Nevertheless, Heracles was able to defeat and kill the monster.

(image source)

Labels:

mechanics,

Writing Mechanics,

Writing Tips

Wednesday, August 17, 2011

Narrative Verb Tense

In oral speech, people often switch freely back and forth between past tense and present tense in telling a story. In written English, however, you need to choose one tense for your story - present tense OR past tense - and stick with that. Usually it is easier to tell a story in past tense, but you can create an immediate or vivid quality if you choose to use present tense instead.

To get a sense of the difference, you can compare these two versions of a fable, one in present tense and one in past tense:

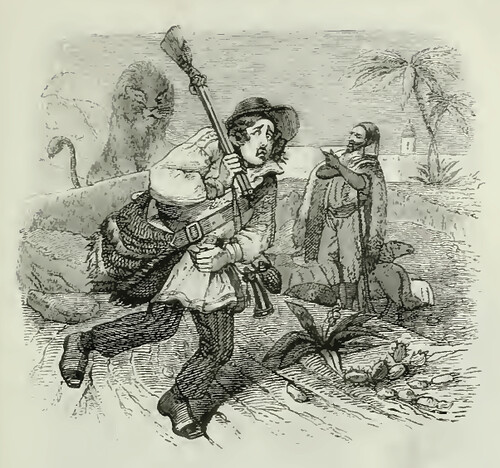

Past Tense. A hunter, who was not really all that brave, decided to track a lion. As he followed the lion's tracks, he met a man who was chopping wood in the forest. He asked the man if he had noticed the lion's tracks or if he knew where the lion's den was. The man replied, "Oh yes, I know about that lion - in fact, I can show you the lion himself if you want." The hunter turned very pale and his teeth began to chatter. "Uh," he said, "no, thank you. I'm just following the lion's tracks; I'm not really looking for the lion himself."

Present Tense. A hunter, who is not really all that brave, decides to track a lion. As he follows the lion's tracks, he meets a man who is chopping wood in the forest. He asks the man if he has noticed the lion's tracks or if he knows where the lion's den is. The man replies, "Oh yes, I know about that lion - in fact, I can show you the lion himself if you want." The hunter turns very pale and his teeth begin to chatter. "Uh," he says, "no, thank you. I'm just following the lion's tracks; I'm not really looking for the lion himself."

Notice that the quoted speech is not affected by the choice of tense for the narrative.

You can find more versions of the Aesop's fable online here.

To get a sense of the difference, you can compare these two versions of a fable, one in present tense and one in past tense:

Past Tense. A hunter, who was not really all that brave, decided to track a lion. As he followed the lion's tracks, he met a man who was chopping wood in the forest. He asked the man if he had noticed the lion's tracks or if he knew where the lion's den was. The man replied, "Oh yes, I know about that lion - in fact, I can show you the lion himself if you want." The hunter turned very pale and his teeth began to chatter. "Uh," he said, "no, thank you. I'm just following the lion's tracks; I'm not really looking for the lion himself."

Present Tense. A hunter, who is not really all that brave, decides to track a lion. As he follows the lion's tracks, he meets a man who is chopping wood in the forest. He asks the man if he has noticed the lion's tracks or if he knows where the lion's den is. The man replies, "Oh yes, I know about that lion - in fact, I can show you the lion himself if you want." The hunter turns very pale and his teeth begin to chatter. "Uh," he says, "no, thank you. I'm just following the lion's tracks; I'm not really looking for the lion himself."

Notice that the quoted speech is not affected by the choice of tense for the narrative.

You can find more versions of the Aesop's fable online here.

Labels:

mechanics,

Writing Mechanics,

Writing Tips

Tuesday, August 16, 2011

Five Uses of "So" in English

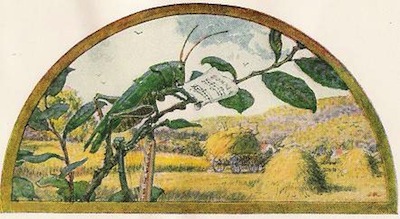

Although it is a very tiny word, "so" has many different uses in English. In fact, "so" can take on three completely different roles: it can be an interjection, an adverb, or a conjunction, and as a conjunction it can introduce two very different types of clauses, purpose and result. The information below should help you sort out these common uses of "so" in English, along with the punctuation rules that go with each one.

1. SO (interjection). The word "so" is often used as an interjection, providing a kind of loose introduction to the sentence that does not convey a specific meaning. Instead, it just signals a nice and easy transition to get the sentence going:

2. SO (adverb) = ALSO. You can use "so" in a sentence with the same meaning as "also, likewise, similarly."

3. SO (adverb) + adjective (THAT). A very common use of "so" is to intensify an adjective or an adverb. Here is an example with an adjective:

4. SO = conjunction introducing purpose clause. You can use "so" to begin a purpose clause that expresses the reason why something is done, the purpose of some action. When the "so" clause expresses purpose, you do not need a comma:

5. SO = conjunction introducing result clause. You can also use "so" to begin a result clause, expressing the consequences of some action. This construction DOES require a comma:

The comma here is very important! That is how you tell the difference between a "so" purpose clause and a "so" result clause: the purpose clause does not have a comma, but the result clause does. The presence or absence of the comma changes the meaning of the sentence.

SUMMARY: If you are using "so" as an interjection at the beginning of a sentence, you need a comma, and you also need a comma if "so" is introducing a result clause. The other uses of "so" in English do not require a comma.

1. SO (interjection). The word "so" is often used as an interjection, providing a kind of loose introduction to the sentence that does not convey a specific meaning. Instead, it just signals a nice and easy transition to get the sentence going:

- "So, you are telling me to work hard like you, Mister Ant, is that it?" asked the grasshopper.

2. SO (adverb) = ALSO. You can use "so" in a sentence with the same meaning as "also, likewise, similarly."

- The ant is a tiny insect, and so is the grasshopper.

3. SO (adverb) + adjective (THAT). A very common use of "so" is to intensify an adjective or an adverb. Here is an example with an adjective:

- The summer sun is so hot!

- The summer sun is so hot that the grasshopper rests in the shade instead of working.

- During the summer, the ant gathers food so diligently that he has enough to last all winter.

4. SO = conjunction introducing purpose clause. You can use "so" to begin a purpose clause that expresses the reason why something is done, the purpose of some action. When the "so" clause expresses purpose, you do not need a comma:

- The ant gathers food in the summer so he will have enough food for the winter.

5. SO = conjunction introducing result clause. You can also use "so" to begin a result clause, expressing the consequences of some action. This construction DOES require a comma:

- The grasshopper did not gather food in summer, so he did not have anything to eat in winter.

The comma here is very important! That is how you tell the difference between a "so" purpose clause and a "so" result clause: the purpose clause does not have a comma, but the result clause does. The presence or absence of the comma changes the meaning of the sentence.

SUMMARY: If you are using "so" as an interjection at the beginning of a sentence, you need a comma, and you also need a comma if "so" is introducing a result clause. The other uses of "so" in English do not require a comma.

Labels:

mechanics,

Writing Mechanics,

Writing Tips

Monday, August 15, 2011

Commas and Relative Clauses

Sometimes you set off relative clauses with commas, but when the clause is ESSENTIAL to the meaning of the sentence, you do not use commas. (This is also true for other kinds of clauses, not just relative clauses.) Here are some examples:

Here you see Arachne's contest with Athena; visit the Bestiaria for more information.

- ESSENTIAL. Arachne was a human weaver who challenged the goddess Athena to a weaving contest.

(The "who" clause is an essential part of the sentence; without that clause, the sentence does not convey its main idea.) - NON-ESSENTIAL. Arachne, who was a talented weaver, challenged the goddess Athena to a weaving contest.

(The "who" clause provides useful information, but the clause is not essential to the sentence; if you leave it out, the sentence still conveys the main idea.)

Here you see Arachne's contest with Athena; visit the Bestiaria for more information.

Labels:

mechanics,

Writing Mechanics,

Writing Tips

Sunday, August 14, 2011

Commas as Parentheses

You can use commas like parentheses, wrapping around a word or phrase or clause inside a sentence - provided that the word or phrase or clause is something extra, something that is not essential to the meaning of the sentence. Here are some examples:

To find out more about the three goddesses vying for the favor of Paris, see Wikipedia.

- The "Judgment of Paris," a scene depicted in many paintings, shows Paris choosing between three goddesses: Hera, Athena, and Aphrodite.

- Paris, who was a prince of Troy, must decide which of the goddesses is the most beautiful.

- Each of the goddesses, convinced of her own great beauty, offers to give Paris a reward in order to win the contest.

- Paris, unable to resist Aphrodite's offer, declares that she is the most beautiful.

- His prize is Queen Helen of Sparta, the wife of King Menelaus, and she is known forever after as "Helen of Troy."

- Paris, however, will come to regret these events because they lead to the Trojan War and the utter destruction of the Trojans as a people.

- If you leave the word/phrase/clause out, does the sentence still make sense?

- Is there a kind of "bump" or "pause" in the flow of the sentence because of the word/phrase/clause?

- Can you safely move the word/phrase/clause somewhere else in the sentence without changing its meaning?

To find out more about the three goddesses vying for the favor of Paris, see Wikipedia.

Labels:

mechanics,

Writing Mechanics,

Writing Tips

Saturday, August 13, 2011

Commas and Final Elements (Free Modifiers)

Sometimes a sentence will have what is called a "free modifier" at the end. This is a phrase that refers back to something earlier in the sentence, and it is called a "free modifier" because you can actually move the phrase somewhere else in the sentence without changing the meaning. When you have a free modifier phrase at the end of a sentence, it is set off with a comma.

Here is an example of a free modifier at the end of a sentence:

Here, on the other hand, is an example of a sentence where the modifier is not free, which means you do not use a comma:

For more information about commas, see Purdue's OWL.

Visit Wikipedia for more information about Hercules and the Hydra. In this image, you can also see the crab attacking Hercules from behind, too!

Here is an example of a free modifier at the end of a sentence:

- Hercules killed the monstrous hydra, chopping off all nine of its heads.

Here, on the other hand, is an example of a sentence where the modifier is not free, which means you do not use a comma:

- Hercules saw the monstrous hydra swimming beneath the surface of Lake Lerna.

For more information about commas, see Purdue's OWL.

Visit Wikipedia for more information about Hercules and the Hydra. In this image, you can also see the crab attacking Hercules from behind, too!

Labels:

mechanics,

Writing Mechanics,

Writing Tips

Subscribe to:

Posts (Atom)